In the previous section, I spent a substantial amount of time covering the definition of what a blockchain is, from the perspective of distributed systems literature. For those looking for a concise summary, I claimed the following:

The networks that we consider as “blockchains,” in reality, are just distributed databases that are updated using a blockchain. Virtual machines, then, are (at a fundamental level) responsible for updating the database upon recieving a new block.

Some might consider the previous post to be a bit pedantic, but I believe that my elaborations provide the foundation necessary for what we will be going over in the next two posts: a virtual machine implementation designed to host a chess platform.

Aside: State Machine Replication <> Blockchains

Having covered blockchains from the perspective of distributed systems literature, it is easy now to go over the concept of virtual machines as well. Consider a perfect server; that is, a server that is guaranteed to never go down. Like any server, this server is designed with a specific purpose in mind, and so let’s assume that this server is running an instance of the EVM. Under this scenario, a virtual machine is synonymous with traditional servers in that it receieves a client request, executes said request, and returns the result in the client.

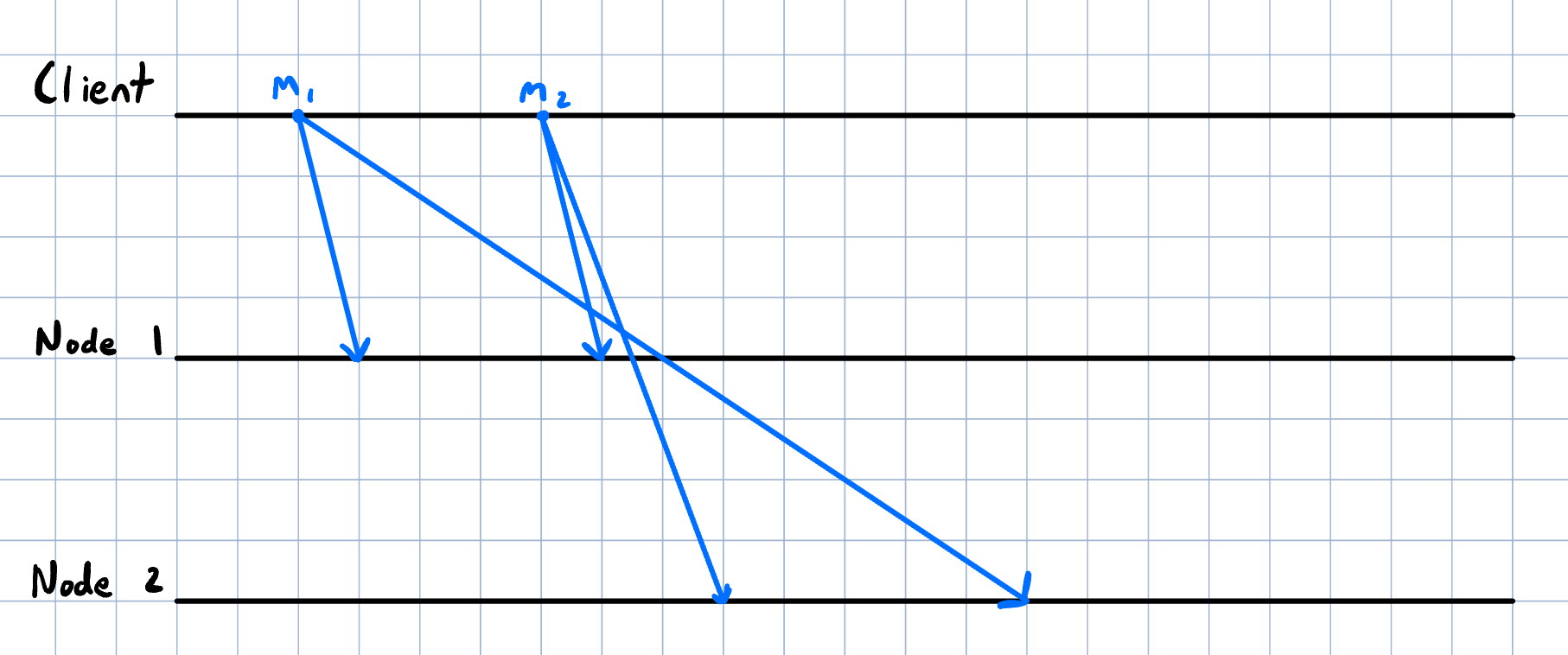

Although a perfect server would be a lovely thing to have in the world, there’s just one small issue: perfect servers don’t exist. Servers crash and/or go offline and therefore, there needs to exist a way for the state of our server to continue existing even if our server goes down. For this, we look to state machine replication; instead of hosting the state of our application on one node, we host it on several node. Therefore, if we expect at most node to crash, and we have at least nodes in our network, than we can expect for the state of our application to exist on at least one node. Under this model, clients now just send their requests to all nodes in the network, each online node will execute said request, and will send a reply back to the client. However, consider the following situation:

Here, we have three actors: a client and two server nodes. Furthermore, let’s define messages as follows:

- : write at slot of contract

- : write at slot of contract (where )

The client in this scenario sends out in that order and expects that after both operations, regardless of which server it queries, that slot of contract will be . However, this assumes that communication channels between nodes (clients and servers) are FIFO; in the real world, this is not the case. As the image above demonstrates, there exists a case where node 1 receives while node 2 receives . Thus, if the client were to query nodes 1 and 2 after each node have executed their operations, the client would see that there is a disagreement in the network over the value at slot of contract . As it might become apparent, the virtual machine’s sole responsibility of executing client requests is not sufficient; virtual machines also need to come to consensus regarding which state their database should be.

We can go about different ways which we can create a consensus mechanism for which nodes can come to agreement regarding their states. However, we can instead let an external actor take care of this for us and help whenever necessary. In this case, the external actor is AvalancheGo which manages the consensus mechanism for us and asks for the virtual machine to satisfy the following:

- Notify of the possibility of a block being able to be produced

- Produce and deliver a block when asked to

- Execute the necessary state transition upon receipt of an accepted block

Now understanding the new responsibilities of a virtual machine, we are now ready to look at the architectures of TimestampVM and ChessVM; both architectures, in addition to executing client requests whenever possible, are also designed to interact with AvalancheGo in order to facilitate the network consensus process.

TimestampVM Architecture

Before covering the architecture of ChessVM, it is first important to discuss TimestampVM, the virtual machine which ChessVM forks. When discussing about TimestampVM in the Avalanche documentation, I wrote the following:

In contrast to complex VMs like the EVM which provide a general-purpose computing environment, TimestampVM is much, much simpler. In fact, we can describe the goal of TimestampVM in two bullet points:

- To store the timestamp when each block was appended to the blockchain

- To store arbitrary payloads of data (within each block)

While the intent of the virtual machine is relatively simple, we still need to create an architecture which incorporates the following actors: clients which make read requests and write proposals, the consensus process (i.e. AvalancheGo), and the virtual machine itself (i.e. the node), which is responsible for updating its own database. Trying to describe the architecture of TimestampVM with just words can be extremely verbose, and looking at the codebase itself is even worse. Therefore, it is best if we look at the architecture visually:

flowchart LR

client["Client"] <--Commands/Replies--> ch

subgraph TimestampVM[TimestampVM Architecture]

subgraph handlers[APIs]

ch["Chain Handlers"]

sh["Static Handlers"]

end

subgraph VM

v_blk_db[(Verified Block Database)]

a_blk_db[(Accepted Block Database)]

end

ch <--Data--> VM

end

ago(((AvalancheGo))) <--Blocks--> VM We elaborate on the most important components of the TimestampVM architecture:

Timestamp Chain Handlers

The chain handler is responsible for providing a list of gRPC functions which a client can call; upon an execution of one of these functions, the chain handler is responsible for either returning immediately1 (in the case of a read request) or submitting a proposal to the VM which is (hopefully) execution via inclusion in a chosen block. In the case of TimestampVM, we can find the list of supported gRPC functions below:

#[rpc]

pub trait Rpc {

/// Pings the VM.

#[rpc(name = "ping", alias("timestampvm.ping"))]

fn ping(&self) -> BoxFuture<Result<crate::api::PingResponse>>;

/// Proposes the arbitrary data.

#[rpc(name = "proposeBlock", alias("timestampvm.proposeBlock"))]

fn propose_block(&self, args: ProposeBlockArgs) -> BoxFuture<Result<ProposeBlockResponse>>;

/// Fetches the last accepted block.

#[rpc(name = "lastAccepted", alias("timestampvm.lastAccepted"))]

fn last_accepted(&self) -> BoxFuture<Result<LastAcceptedResponse>>;

/// Fetches the block.

#[rpc(name = "getBlock", alias("timestampvm.getBlock"))]

fn get_block(&self, args: GetBlockArgs) -> BoxFuture<Result<GetBlockResponse>>;Timestamp VM

From the previous section, read requests (i.e. the functions ping(), last_accepted(), get_block()) only require us to read into the state of the VM and therefore, the VM itself does not do much with respect to these types of operations. However, things start to get interesting when we consider the propose_block() function; in TimestampVM, the propose_block() function proposes to add a byte-array to the state of the system (by wrapping said byte-array in a block and then appending that block to the stored blockchain). Therefore, for a client’s call of propose_block() to go through, the VM needs to propose the neccessary block to AvalancheGo and execute the neccessary state changes once AvalancheGo marks the block as accepted (assuming it does).

ChessVM Architecture

Given that ChessVM is a fork of TimestampVM and its architecture is more sophisticated, we will again use a visual representation:

flowchart LR

client["Client"] <--Commands/Replies--> ch

subgraph ChessVMA[ChessVM Architecture]

subgraph handlers[APIs]

ch["Chain Handlers"]

sh["Static Handlers"]

end

subgraph VM

v_blk_db[(Verified Block Database)]

a_blk_db[(Accepted Block Database)]

ch_db[(Chess Game Database)]

end

ch <--Transactions--> VM

end

ago(((AvalancheGo))) <--Blocks--> VM Although the visual elaboration of the ChessVM architecture looks similar to that of TimestampVM, there are some major differences:

- In the case of write proposal, we are not simply sending a byte-array over to the VM. Rather, we create a transaction associated with the write proposal of the client and submit it to the VM.

- In addition to separating the storage of verified and accepted blocks, we are also reserving storage for chess games.

Just like with TimestampVM, we will touch on the important components that define ChessVM:

Chess Chain Handlers

Below is the list of available gRPC methods that clients are able to call:

#[rpc]

pub trait Rpc {

/// Pings the VM.

#[rpc(name = "ping", alias("chessvm.ping"))]

fn ping(&self) -> BoxFuture<Result<crate::api::PingResponse>>;

/// Fetches the last accepted block.

#[rpc(name = "lastAccepted", alias("chessvm.lastAccepted"))]

fn last_accepted(&self) -> BoxFuture<Result<LastAcceptedResponse>>;

/// Fetches the block.

#[rpc(name = "getBlock", alias("chessvm.getBlock"))]

fn get_block(&self, args: GetBlockArgs) -> BoxFuture<Result<GetBlockResponse>>;

// RPCs specific to ChessVM

/// Creates new Chess game

#[rpc(name = "createGame", alias("chessvm.createGame"))]

fn create_game(&self, args: CreateGameArgs) -> BoxFuture<Result<CreateGameResponse>>;

/// Make a Chess move

#[rpc(name = "makeMove", alias("chessvm.makeMove"))]

fn make_move(&self, args: MakeMoveArgs) -> BoxFuture<Result<MakeMoveResponse>>;

/// End a Chess game

#[rpc(name = "endGame", alias("chessvm.endGame"))]

fn end_game(&self, args: EndGameArgs) -> BoxFuture<Result<EndGameResponse>>;

/// Get Chess game state

#[rpc(name = "getGame", alias("chessvm.getGame"))]

fn get_game(&self, args: GetGameArgs) -> BoxFuture<Result<GetGameResponse>>;

}In addition to the functions ping(), last_accepted(), and get_block(), we see four additional gRPC functions. These functions expose the behaviors necessary for clients to interact with ChessVM; that is, we provide clients with a way to create chess games, to make moves on an existing chess board, to end an existing chess game, and to get the state of an existing chess game.

With the exception of get_game(), which is inherently a read-only function, each of the remaining ChessVM gRPC functions, while all being write proposals, each modify the state of the system in different ways. Therefore, we need to introduce the concept of transactions which abstract the different write proposals as simply actions. These “actions” are then passed onto the VM whose job is to then execute them.

Chess VM

Upon receiving a transaction from a client (via the chain handler), the VM first caches the transaction by storing it in its local mempool. From here, there exist two cases (let be the minimum number of transactions required in a ChessVM block):

- If the node’s mempool has elements, the node notifies AvalancheGo that it is ready to produce a block.

- If the node’s mempool has less than elements, it does nothing

In the former case, once we notify AvalancheGo that we are ready to produce a block, and AvalancheGo accepts our request, we create a block that, in contrast to simply wrapping a byte-array like in TimestampVM, now contains a list of transactions.

Verifying Blocks

Having now an idea of how a client action can eventually be included in a block (in the case of a write proposal), we now need to consider the following: we only want valid transactions to be included in our block. That is, we do not to include client actions that, if executed, cause an instance of ChessVM to crash. We can abstract this invariant even further by stating the following: we only want to append blocks which do not violate any invariants of the system. Examples of this include the following:

- We do not want to append blocks whose parent block is not the same as the current block

- We do not want to append blocks whose timestamp is less than the timestamp of any existing, accepted block

- We do not want to append blocks which have already been accepted

- We do not want to append blocks which contain a transaction whose execution leads to a node crashing

In both TimestampVM and ChessVM (which implemenent the SnowmanVM interface), each block contains the function verify() which, when called, checks if said blocks adheres to the invariants of the system.

Accepting Blocks

After a block has been produced and passed onto the consensus engine, we now consider the following question: who executes the block once it has been accepted by the consensus engine? As surprising as it may seem, the VM does not execute the necessary state changes, but rather the block itself! To understand why, let’s consider an arbitrary block:

classDiagram

class Block {

+int timestamp

+ptr database

+list transactions

+accept()

+verify()

} The block definition above, which is non-exhaustive, contains field that relate to its state (in particular, timestamp and transactions). However, there is also an additional field that may come as a surprise to many: a pointer to the node’s database. The reason that we need a pointer to the node’s database is by design of the accept() function; when called by the consensus engine, the accept() function needs to execute all state transitions associated with the block. Therefore, since accept() is a function of the block and not of the VM, all blocks need a pointer to the database itself.

In both TimestampVM and ChessVM, all logic relating to executing write proposals (like storing an accepted block or modifying the state of a chess game) are behaviors of the block. Notice by designing blocks in this manner, AvalancheGo is able to start any necessary state transitions without calling the VM; this leads to the following architecture (in the case of a 3-node network):

flowchart LR

subgraph node1[Node 1]

ago1[AvalancheGo]

subgraph vm1[VM]

db1[(Database)]

end

vm1 <--Blocks--> ago1

end

subgraph node2[Node 2]

subgraph vm2[VM]

db2[(Database)]

end

ago2[AvalancheGo]

ago2 <--Blocks--> vm2

end

subgraph node3[Node 3]

ago3[AvalancheGo]

subgraph vm3[VM]

db3[(Database)]

end

ago3 <--Blocks--> vm3

end

ago2 <--Blocks--> ago3

ago1 <--Blocks--> ago2

ago1 <--Blocks--> ago3 The virtual machine is still responsible for maintaining its associated database, but it now delegates the responsibility of conduct state transitions to the block. Since blocks that will be appended to the blockchain are handled by AvalancheGo, we can imagine an instance of AvalancheGo consisting of the VM itself and a sets of verified blocks which are being considered to be appended.

Lifetime of a ChessVM Transaction

Below is a timeline of how a transaction in ChessVM goes from a command to eventually being executed (we assume a node’s mempool has a capacity of ):

- A client submits a gRPC command to an instance of ChessVM

- The receiving node, upon delivery of , creates a transaction which contains and submits it to its own mempool

- The node then notify its instance of AvalancheGo that it is ready to build a block

- The local instance of AvalancheGo is notified and tells the node to produce a block

- The local node produces a block, checks its validity and if valid, returns the block to AvalancheGo

- Assuming there is no disagreement in the consensus process, AvalancheGo calls

accept()on the accepted block; the accepted block makes the necessary state transitions

Wrapping Up (For Now)

In this article and the previous one, we have gone from thinking of distributed systems like Avalanche as solely blockchains to realizing the use case of blockchains as a component in distributed systems. Furthermore, its become obvious that VMs are not just servers that execute client requests; they are also responsible for communicating with its local consensus process to eventually come to agreement with the majority of the network on the world sate.

At this point, there are many different paths which one can go about with ChessVM; the most natural progression would be to provide a low-level specification on the implemenation of ChessVM. However, as I mentioned at the beginning of this series, building a custom VM is hard; furthermore, while one can learn as much about VMs as they want, part of the process of becoming proficient with VMs is to make mistakes and learn from them. Therefore, part three (i.e. the last post) of the ChessVM series will be dedicated to discussing some (but not all) of the major mistakes and misunderstandings that I made/had while building out ChessVM.

Footnotes

-

Immediately in the sense that we do not have to rely on the blockchain for the read request to go through. Rather, we need to obtain read access into the VM database. ↩